How QoE Findings Shape the Deal (5/5)

Connecting financial analysis to valuation, price mechanisms, and risk allocation

written by

Quality of earnings analysis is never an end in itself.

Every adjustment, every finding, every flag in a due diligence report exists to answer a commercial question: what is this business worth, and what risks am I taking on?

I have seen deals where a single QoE adjustment moved the purchase price by tens of millions. I have seen transactions where findings that seemed minor in isolation combined to fundamentally reshape the economics. And I have seen post-close disputes that traced directly back to issues that were visible in the numbers but not adequately addressed in the documentation.

This article brings together everything we have covered in this series and shows how it connects to deal outcomes. The goal is to help you understand that financial due diligence is a commercial exercise, not an academic one.

The numbers matter because they translate into money that changes hands.

The valuation anchor: why adjusted EBITDA matters

In most private company transactions, enterprise value is calculated as a multiple of EBITDA. The specific multiple reflects the buyer's view of growth prospects, risk profile, and competitive dynamics. But the EBITDA figure itself comes from the quality of earnings analysis.

This is why adjusted EBITDA is the valuation anchor.

A €500k downward adjustment to EBITDA at a 10x multiple reduces enterprise value by €5 million. At a 15x multiple, the same adjustment costs €7.5 million.

The mechanical relationship is simple. The judgment involved in establishing the right EBITDA figure is not.

What adjusted EBITDA represents

Adjusted EBITDA should reflect the sustainable, recurring earnings power of the business under normal operating conditions.

It removes one-off items that will not recur. It normalises costs to market rates. It adjusts for any timing distortions that make the historical period unrepresentative.

The adjusted figure becomes the baseline for projecting future performance. If the buyer's model assumes 10% annual EBITDA growth off a base of €10 million, and the true base is actually €8.5 million, every year of the projection is overstated. The terminal value in the DCF is overstated. The return calculation is wrong.

This is why buyers care so much about getting the adjusted EBITDA right. It is not pedantry. It is the foundation of the entire investment case.

The seller's perspective

Sellers naturally want the highest defensible EBITDA figure. This is rational. Higher EBITDA means higher valuation and more proceeds.

The tension in every deal is finding the adjustment package that both parties can accept.

Seller advisors (who prepare vendor due diligence reports) tend to be aggressive in adding back costs and conservative in making negative adjustments. Buyer advisors push in the opposite direction.

In practice, the final adjusted EBITDA usually lands somewhere between the VDD figure and the ADD figure. The negotiation determines exactly where.

Two categories of findings: EV impact versus contingent risk

Not all due diligence findings affect enterprise value directly. Understanding the distinction helps you see how findings flow through to deal terms.

Findings that adjust EV

Some findings directly change the maintainable EBITDA, and therefore enterprise value. These include:

Revenue quality issues. If a material portion of revenue is non-recurring or at risk of churn, the sustainable revenue base is lower than reported. Lower revenue means lower EBITDA.

Cost normalisations. Below-market founder salaries, deferred maintenance, run-rate cost step-ups. These all reduce the maintainable EBITDA below reported levels.

One-off removals. Litigation costs, restructuring charges, transaction fees. These increase EBITDA by removing costs that will not recur.

When the buyer and seller agree on these adjustments, the impact flows directly into the price. The enterprise value calculation uses the adjusted EBITDA, and the negotiations proceed from there.

Findings that create contingent risk

Other findings do not change EBITDA but create potential future liabilities. These get addressed through different mechanisms.

Pending litigation. A lawsuit that might result in a €500k payment does not reduce EBITDA. But the buyer does not want to absorb that risk at full value.

Tax exposures. An aggressive tax position that could be challenged by authorities represents a contingent liability, not an earnings adjustment.

Contractual risks. Change of control provisions, customer termination rights, supplier repricing clauses. These might never crystallise, but they represent real exposure.

These findings typically get addressed through one of three mechanisms: net debt adjustments (if the liability is probable and quantifiable), warranty and indemnity protection (if the seller should bear the risk), or purchase price reduction (if the buyer simply refuses to take the risk at the offered price).

The skilled advisor helps the client understand which mechanism is appropriate for each finding and how to structure the ask.

The EV to equity bridge

Enterprise value is what the business is worth. Equity value is what the buyer actually pays for the shares. The bridge between them is where much of the QoE analysis lands.

The basic formula is straightforward:

Equity Value = Enterprise Value − Net Debt − Debt-like Items + Cash-like Items ± Working Capital Adjustment

Each component involves judgment calls that can materially affect the price.

Net debt definition

Net debt in an acquisition context is broader than net debt on the balance sheet. It includes financial debt less cash, but also any other items that represent claims on the business or excess assets that transfer to the buyer.

I have seen net debt definitions that included:

Provisions for restructuring that will require cash post-close. Onerous lease obligations. Deferred consideration from prior acquisitions. Transaction bonuses payable at close. Tax liabilities not reflected in working capital. Dividend declarations that have not yet been paid.

Every item added to net debt reduces the equity cheque. The negotiation over what belongs in net debt is one of the most commercially significant discussions in any deal.

Working capital adjustment

The working capital mechanism ensures the buyer receives a business with a "normal" level of operating assets and liabilities.

If the seller has run down inventory or stretched payables to generate cash before closing, the buyer receives a depleted business. The working capital adjustment corrects for this by comparing actual working capital at closing to a target (usually based on historical averages).

Working capital below target means the seller owes the buyer. Working capital above target means the buyer owes the seller.

The definition of normalised working capital and the calculation of the target are intensely negotiated. A €1 million difference in the target is a €1 million difference in the equity price.

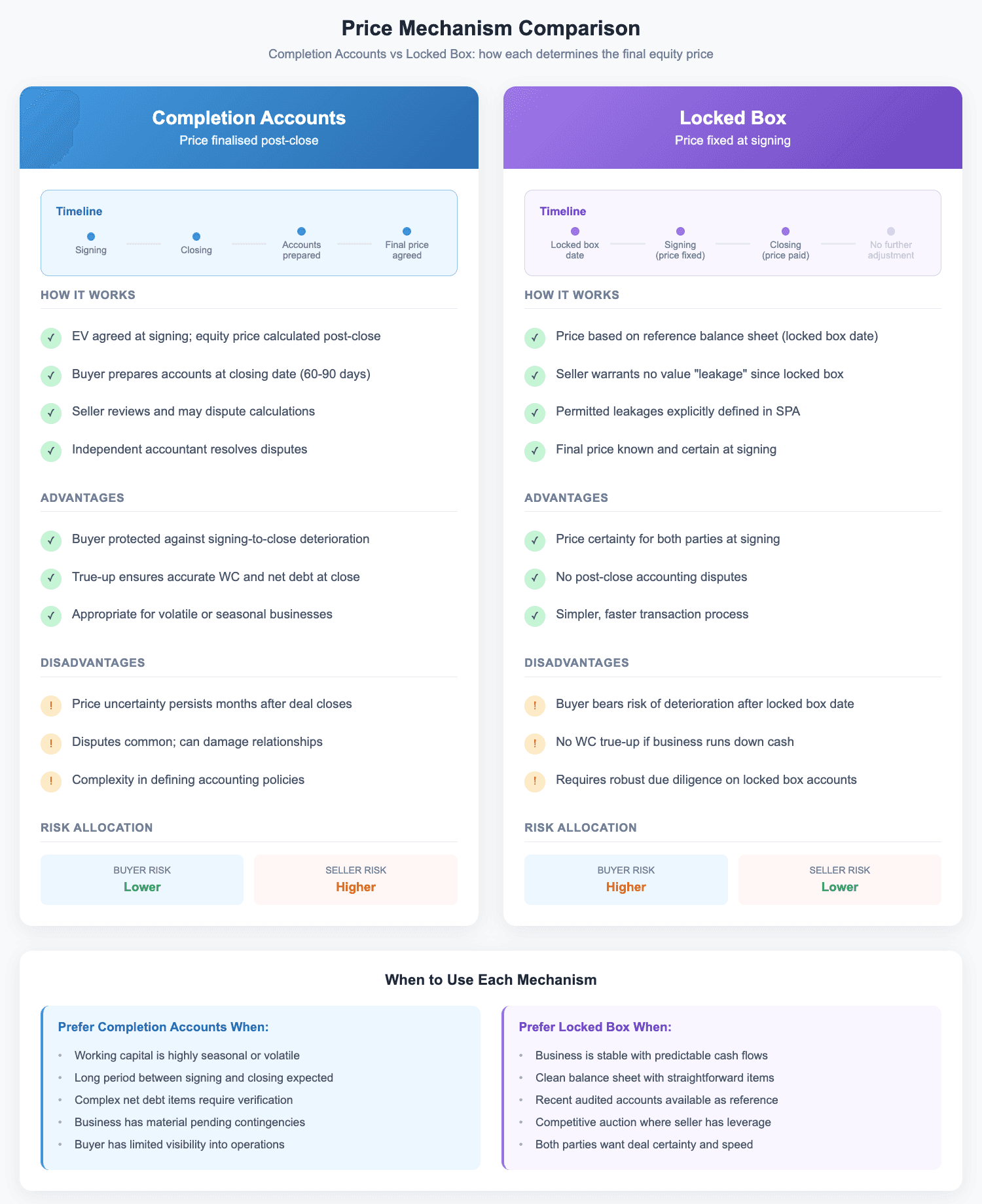

Price mechanisms: completion accounts versus locked box

The choice of price mechanism determines how the EV to equity bridge gets calculated and when certainty is achieved.

Completion accounts

Under a completion accounts mechanism, the parties agree on enterprise value at signing. The equity price is then calculated after closing based on actual net debt and working capital at the closing date.

The buyer prepares completion accounts, typically within 60 to 90 days of closing. The seller has the right to review and dispute. If they cannot agree, the disputed items go to an independent accountant for determination.

Completion accounts protect the buyer against deterioration between signing and closing. They also ensure the buyer receives exactly the net debt and working capital position reflected in the price.

The downside is uncertainty. Neither party knows the final price until well after the deal closes. Disputes are common and can take months to resolve.

Locked box

Under a locked box mechanism, the equity price is fixed at signing based on a reference balance sheet date (the "locked box date"), typically the most recent audited accounts.

The seller warrants that no value has leaked from the business between the locked box date and closing. Permitted leakages (normal course dividends, management fees, intercompany charges) are explicitly defined. Any non-permitted leakage is a breach.

Locked box provides price certainty. The buyer knows exactly what they are paying at signing. The seller knows exactly what they are receiving.

The risk shifts to the buyer. If the business deteriorates between the locked box date and closing, the buyer bears the loss. If working capital runs down, the buyer has no true-up mechanism.

How QoE informs the choice

QoE findings influence which mechanism is appropriate.

If working capital is volatile or seasonal, completion accounts may be necessary to achieve a fair outcome. If net debt items are complex or contingent, the buyer may need post-close verification.

If the business is stable and the balance sheet is clean, locked box offers simplicity and certainty that both parties may prefer.

The QoE analysis gives the buyer the information needed to assess whether they are comfortable taking locked box risk.

SPA protections: warranties, indemnities, and escrow

Due diligence findings that cannot be resolved through price adjustments often get addressed through contractual protections in the sale and purchase agreement.

Warranties and representations

The seller makes statements about the business that the buyer can rely on. If those statements prove false, the buyer has a claim.

Standard warranties cover accuracy of accounts, absence of undisclosed liabilities, compliance with laws, validity of contracts, and similar matters. They provide general protection against unknown issues.

QoE findings often trigger specific warranties. If the due diligence identified a questionable revenue recognition practice, the buyer might require a specific warranty that revenue has been recognised in accordance with applicable standards. If a tax position looks aggressive, the buyer might require a warranty that all taxes have been properly declared and paid.

The warranty package reflects the risk profile revealed by due diligence.

Indemnities

Indemnities provide pound-for-pound protection against specific identified risks. Unlike warranties (which may be subject to limitations), indemnities typically provide full recovery.

QoE findings that identify quantifiable but contingent risks often become indemnity items. Pending litigation with a potential €200k exposure might be covered by a specific indemnity. Tax irregularities identified in due diligence might be indemnified.

The buyer prefers indemnities because recovery is cleaner. The seller prefers warranties with limitations because exposure is capped.

Escrow and holdback

When the buyer does not trust warranty claims alone, they may require funds to be held in escrow or retained from the purchase price.

In one transaction I observed, tax due diligence identified potential penalties of €6.5 million arising from historical positions. The seller disputed the exposure but could not eliminate the risk. The solution was an escrow: €6.5 million held by a third party pending resolution of the tax matters. As matters were resolved favourably, funds were released to the seller.

Escrow provides security but ties up seller proceeds. The amount and duration are negotiated based on the magnitude and timeline of the underlying risks.

An integrated example

Let me walk through how QoE findings might flow through to deal terms in a single transaction.

The situation

A private equity fund is acquiring a B2B services company. The seller's vendor due diligence report shows LTM EBITDA of €4.2 million. The agreed multiple is 8x, implying an enterprise value of €33.6 million.

The buyer's due diligence findings

The buyer's financial due diligence identifies the following:

Revenue adjustments. €180k of revenue in the LTM period related to a one-off project that will not recur. Negative adjustment.

Founder salary normalisation. The founder-CEO drew €120k annually. Market replacement cost is €280k. Negative adjustment of €160k.

Recent hires. Three senior staff hired in the past five months. Only €90k of their annual cost of €270k appears in LTM. Negative adjustment of €180k.

Litigation one-off. €75k of legal fees in LTM related to a now-resolved dispute. Positive adjustment.

Pending litigation. A customer dispute with potential exposure of €150k. Not an EBITDA adjustment, but a contingent risk.

Working capital seasonality. LTM average working capital is €850k. Actual working capital at the proposed closing date is €620k, reflecting seasonal low point.

Tax exposure. Tax due diligence identified an aggressive R&D credit position. Potential exposure €200k if challenged.

The adjusted EBITDA

Item | Adjustment |

|---|---|

VDD EBITDA | €4,200k |

Non-recurring revenue | (€180k) |

Founder salary normalisation | (€160k) |

Recent hires full year | (€180k) |

Litigation one-off | €75k |

ADD EBITDA | €3,755k |

The buyer's adjusted EBITDA is €445k lower than the VDD figure, representing a 10.6% reduction.

The valuation impact

At an 8x multiple, the EBITDA difference implies an enterprise value of €30.0 million versus the seller's €33.6 million. The gap is €3.6 million.

In negotiations, the parties agree to split the difference on certain adjustments. The final agreed EBITDA is €3,900k, implying an enterprise value of €31.2 million.

The EV to equity bridge

Item | Amount |

|---|---|

Enterprise value | €31,200k |

Less: Financial debt | (€2,100k) |

Plus: Cash | €850k |

Less: Working capital adjustment | (€230k) |

Less: Transaction bonuses | (€180k) |

Equity value | €29,540k |

The working capital adjustment of €230k reflects the €850k target versus €620k actual at closing.

The SPA protections

Pending litigation. The €150k customer dispute is covered by a specific indemnity. The seller bears any loss up to the full amount.

Tax exposure. The €200k R&D credit risk is covered by a tax indemnity with a 3-year survival period.

Warranty package. Standard business warranties with an 18-month survival period and a liability cap of €3 million (approximately 10% of equity value).

Escrow. €500k held in escrow for 12 months to secure warranty claims and the specific indemnities.

The outcome

The buyer pays €29.0 million at closing (equity value less escrow). The remaining €540k is held in escrow.

Twelve months later, the customer litigation settles for €80k. The buyer draws €80k from escrow under the indemnity. The remaining €460k is released to the seller.

The final effective price is €29.46 million.

Where QoE disputes emerge post-close

Even well-structured deals can lead to disputes. Understanding where disagreements typically arise helps in structuring protections.

Completion accounts disputes

The most common post-close disputes involve completion accounts calculations. Typical issues include:

Working capital classification. Is a particular accrual working capital (subject to true-up) or net debt (a direct deduction)? The boundary is often contested.

Provision adequacy. Are the provisions in the completion accounts sufficient? The buyer may argue they are understated; the seller may argue they are conservative.

Cut-off adjustments. Were revenues and costs recorded in the correct period? Post-close review often identifies timing issues that affect the completion balance sheet.

Debt-like items. Items that were not identified as net debt during due diligence may emerge as disputed completion account items.

These disputes typically go to independent accountant determination. The accountant is bound by the definitions in the SPA, so the quality of the drafting determines the outcome.

Warranty claims

Warranty claims arise when something the seller warranted proves untrue. Common scenarios include:

Undisclosed liabilities that emerge after closing. Customer contracts that turn out to have terms different from those represented. Compliance issues that were not disclosed. Tax assessments for pre-close periods.

Warranty claims are often contentious because they involve establishing both the breach and the quantum of loss. The buyer must prove the warranty was false and that they suffered damage as a result.

Earn-out disputes

When part of the purchase price is contingent on post-close performance (an earn-out), disputes over the calculation are common.

The seller may argue the buyer deliberately depressed earnings to reduce the earn-out payment. The buyer may argue the targets were missed due to pre-existing issues in the business.

Earn-out structures require extremely precise drafting of the measurement mechanics and the obligations of the parties during the earn-out period.

Information asymmetry and the role of transaction services

Sellers know their business intimately. They know where the bodies are buried. They understand which customers are at risk, which costs are unsustainable, which numbers have been dressed up for the sale.

Buyers start with information asymmetry. They see the data room, the management presentations, the vendor due diligence. But they do not have the institutional knowledge that comes from operating the business.

Transaction services work exists to close this gap.

What VDD reveals and conceals

Vendor due diligence is prepared by advisors engaged by the seller. Their client's interest is in presenting the business favourably.

VDD reports are professionally prepared and generally accurate. But they reflect choices about what to emphasise and what to minimise. Adjustments that increase EBITDA are explained in detail. Adjustments that decrease EBITDA may be buried or omitted.

VDD reports typically do not include findings that would be damaging to the seller's position. If the analysis uncovered a material issue, the seller addresses it before the VDD is released or accepts that buyers will discover it in their own work.

What buy-side due diligence adds

Buy-side due diligence (acquisition due diligence) serves a different master. The advisor's client is the buyer, and the objective is to identify risks and establish an accurate value.

The ADD report will often include adjustments the VDD missed or declined to make. It will flag risks that the VDD minimised. It will stress-test management's assumptions and projections.

The comparison between VDD and ADD tells the buyer where the seller's position is aggressive and where the real negotiation opportunities lie.

The investment committee perspective

Investment committees at private equity funds see both reports. They focus on the differences.

Large gaps between VDD and ADD adjusted EBITDA signal either aggressive seller positioning or genuine disagreement about the business. Either way, the IC wants to understand the issues before approving the investment.

The IC also focuses on findings that create binary risk. A pending lawsuit that could go either way. A customer that might churn. A regulatory change that could affect the business model. These are harder to price than simple EBITDA adjustments.

The TS report shapes the IC's perception of deal risk. A clean report with minor adjustments signals a straightforward transaction. A report full of caveats and open issues signals complexity and negotiation ahead.

What experienced buyers focus on

Over time, buyers develop pattern recognition for which findings matter most.

The earnings cliff

Any finding that suggests current earnings are not sustainable commands attention. Revenue from a contract that is ending. Costs that have been artificially suppressed. Pricing that is above market and will face pressure.

These findings threaten the base case. If EBITDA is going to decline from current levels, the entire investment model is at risk.

The hidden liability

Contingent liabilities that could crystallise post-close represent direct wealth transfer from buyer to the problem. Tax exposures, environmental liabilities, product liability claims, employee litigation.

Experienced buyers ensure these are either priced in, indemnified, or walked away from.

The integration cost

Findings that imply the buyer will need to spend money post-close to maintain the business are effectively negative adjustments even if they do not appear in the QoE.

IT systems that need replacement. Facilities that need upgrade. Management gaps that need filling. These costs come out of the buyer's returns even though they do not reduce the purchase price.

The quality signal

Sometimes the findings themselves matter less than what they signal about the business and its management.

A company with clean books, straightforward operations, and minimal adjustments signals operational competence. A company with complex adjustments, aggressive accounting, and multiple risk areas signals potential problems beyond what the due diligence revealed.

Buyers factor these signals into their overall assessment of the opportunity.

Closing thoughts

Quality of earnings analysis is the translation layer between operating reality and deal economics. Every adjustment represents a judgment about what the business actually earns and what risks transfer with the transaction.

The best practitioners understand that QoE is fundamentally a commercial exercise. Technical accuracy matters, but only because it serves the goal of pricing the business correctly and allocating risks appropriately.

When I finish a due diligence engagement, I want the client to understand three things: what the business actually earns on a sustainable basis, what risks exist that are not reflected in the purchase price, and how to structure the transaction to protect against those risks.

If the QoE analysis answers those questions clearly, it has done its job.

Everything else is detail.

This completes our 5-part series on Quality of Earnings. We have covered what QoE is and why it matters, how to identify and categorise adjustments, how to evaluate revenue quality and sustainability, how to analyse cost structure and operating leverage, and now how these findings shape deal outcomes.

The goal throughout has been to help you see financial due diligence the way experienced practitioners do: as a tool for understanding value and managing risk in transactions.