What Quality of Earnings Actually Means (1/5)

Understanding the gap between reported profit and the earnings a buyer can rely on

written by

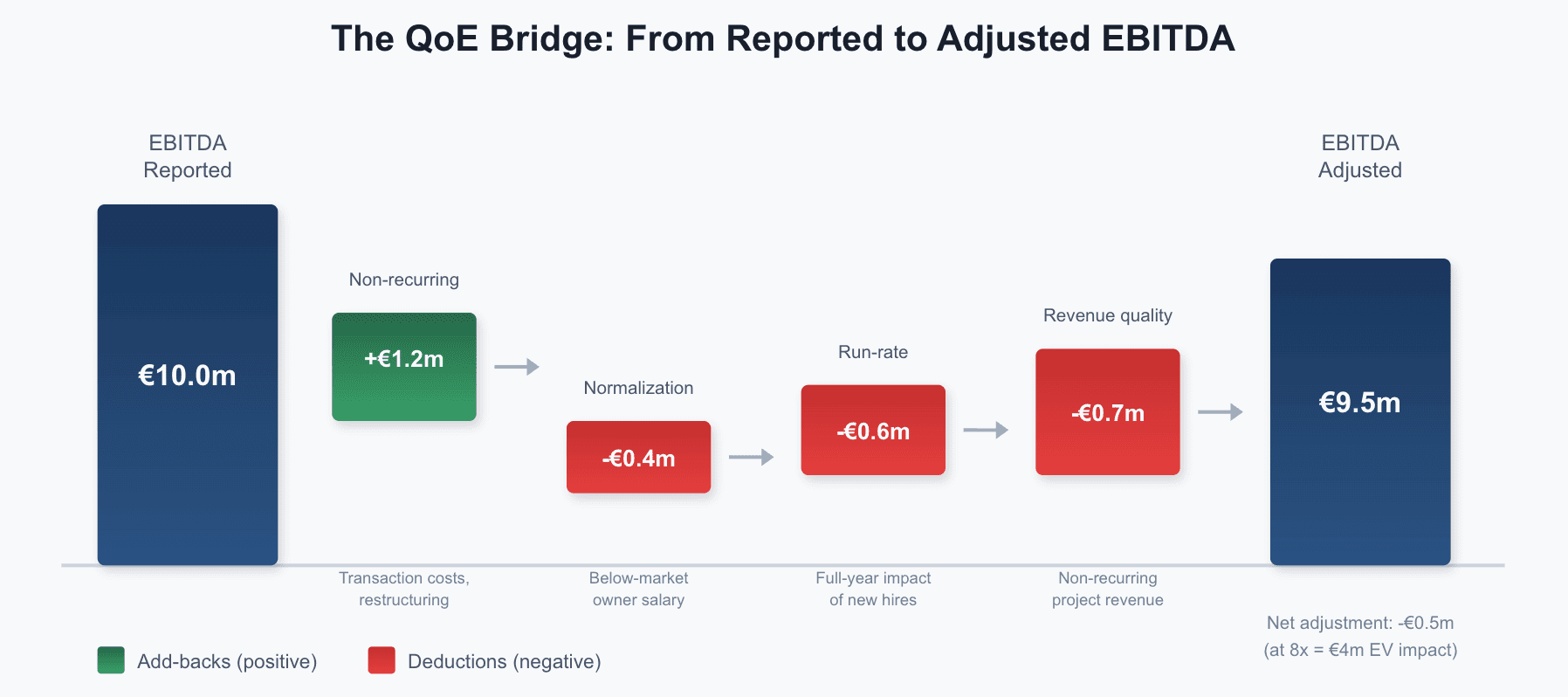

A company reports €10 million EBITDA. The seller values the business at 8x earnings, implying an enterprise value of €80 million. The buyer's advisor completes due diligence and concludes that maintainable EBITDA is closer to €8.5 million. Same company, same accounts, €12 million difference in implied value.

This gap is what Quality of Earnings analysis exists to explain.

The starting point: accounting profit versus economic reality

Financial statements are designed to comply with accounting standards. They answer questions like: did we apply IFRS correctly? Are our recognition policies defensible? Do the auditors agree?

These are important questions. But they are not the questions a buyer asks.

A buyer cares about one thing: what will this business earn for me, starting from the day I own it? That question requires a different lens. It requires stripping away the noise of one-time events, backward-looking adjustments, and accounting choices that obscure the underlying cash-generating capacity of the business.

Quality of Earnings is the bridge between what the accounts say and what the economics mean.

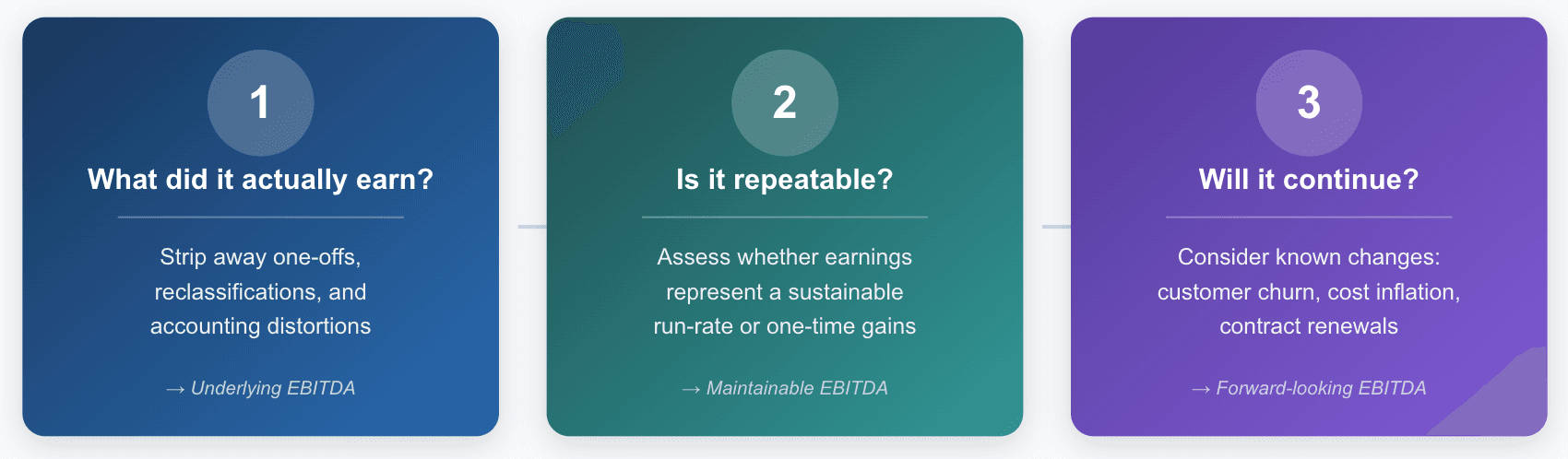

The three questions QoE answers

At its core, QoE analysis is structured around three simple questions.

Every adjustment, every page of analysis, every finding in a due diligence report ultimately ties back to one of these:

1. What did the business actually earn?

Reported EBITDA includes items that may not reflect normal operations. Restructuring costs, litigation settlements, exceptional bonuses, transaction fees. These hit the P&L but distort the picture of underlying performance.

A QoE analysis strips these out to arrive at an "underlying" or "adjusted" EBITDA.

2. Is it repeatable?

Some earnings happen once. A large project that won't recur. A contract that ended. A one-time pricing benefit from a customer relationship that has since terminated.

The question here is: of the earnings that remain after removing one-offs, which ones represent a run-rate that the buyer can rely on going forward?

3. Will it continue?

This is where the analysis becomes forward-looking. A key customer just churned. Input costs are rising. A major contract is coming up for renewal at less favorable terms. These factors may not have hit the historical numbers yet, but they affect what the buyer will actually receive.

This is where QoE overlaps with commercial diligence and forecasting.

Why EBITDA alone tells you very little

If you are new to transaction work, it can be confusing why buyers spend weeks and significant fees analyzing a number that management already reports. The accounts are audited. EBITDA is disclosed. What is there to investigate?

The answer is that EBITDA on its own is a deeply incomplete measure.

Consider a business reporting €12 million EBITDA. Now layer in the following facts:

The company recognized €1.5 million of revenue from a project that has no likelihood of recurring

Founder compensation was €200,000, where market rate for a replacement CEO would be €500,000

€800,000 of IT infrastructure costs were deferred into the following year to hit budget

A large customer representing 18% of revenue churned two months after year-end

None of these items change the reported EBITDA. All of them change what a buyer should pay.

This is why the concept of "pro forma" or "adjusted" EBITDA exists. And this is why buyers commission independent advisors to rebuild the number from the ground up, rather than relying on what management chooses to present.

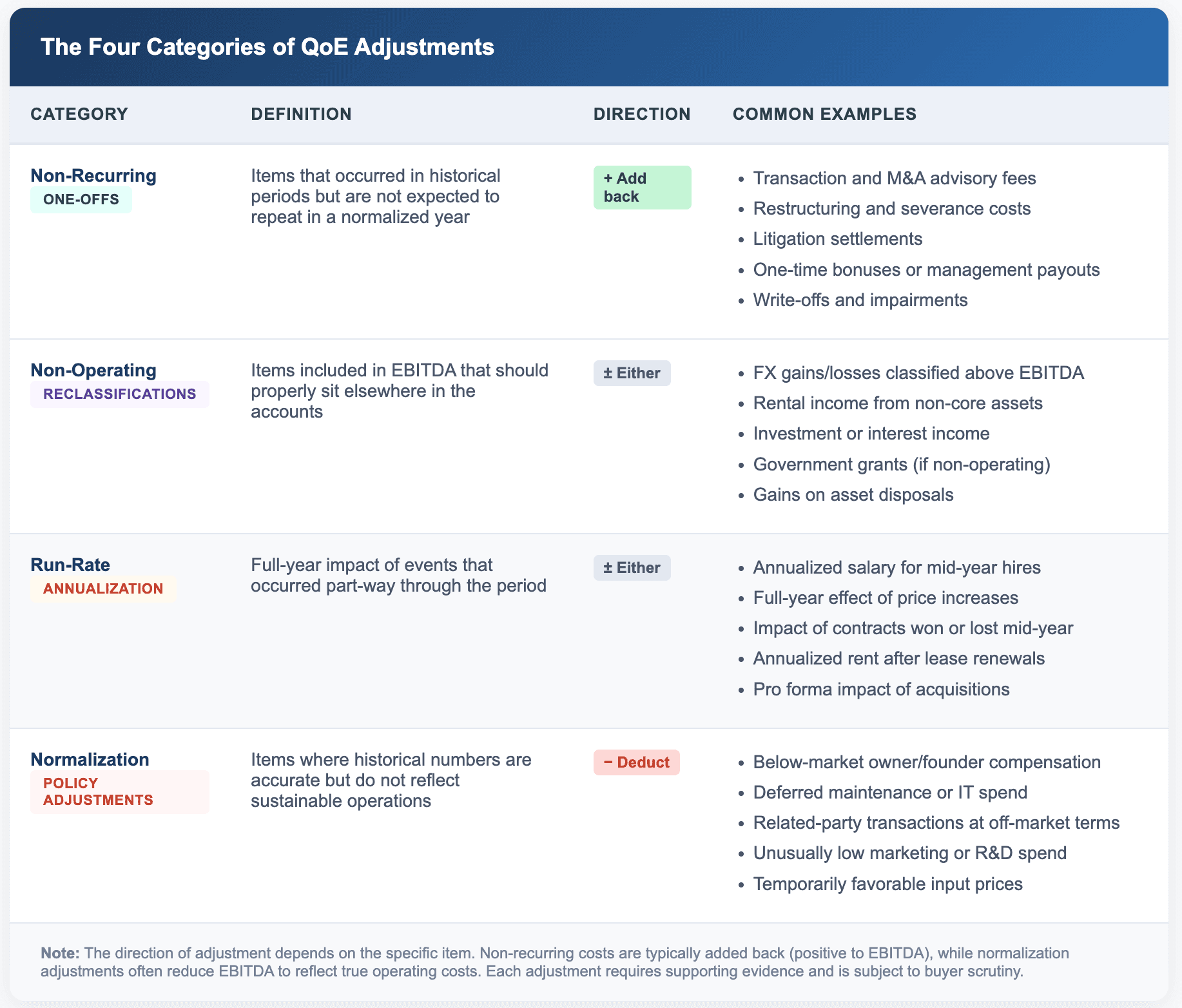

The categories of adjustment

QoE adjustments generally fall into four buckets. Understanding these categories helps you see the logic behind the numbers, even when the specific adjustments vary deal to deal.

1. Non-recurring items

These are costs or income items that occurred in the historical period but are not expected to repeat. Transaction costs, restructuring charges, legal settlements, one-off bonuses, M&A-related fees. The defining characteristic is that they are genuinely exceptional and would not be expected in a normalized year of operations.

In practice, this category attracts a lot of skepticism from buyers. Sellers sometimes have an incentive to categorize ordinary-course fluctuations as "non-recurring" to inflate adjusted EBITDA. A TS advisor's job is to pressure-test these claims.

2. Non-operating items

Some items that flow through the P&L above EBITDA should properly sit elsewhere.

Foreign exchange gains or losses that management has included in operating income. Rental income from property that is not core to the business. Investment income or one-off grants.

These are not adjustments for things that happened once; they are reclassifications of items that should never have been in EBITDA in the first place.

3. Run-rate adjustments

This is where the analysis becomes forward-looking. Run-rate adjustments capture the full-year impact of events that occurred part-way through the historical period. A new hire in September whose full salary will hit next year. A price increase that took effect in Q3. A contract that terminated mid-year.

The logic is simple: if you are valuing the business on its current-year EBITDA, but something changed mid-year, you need to normalize for the annualized effect.

4. Normalization and policy adjustments

These adjustments address situations where the historical numbers are accurate but misleading. A founder-owned business where the owner took below-market compensation. A company that deferred maintenance capex to boost short-term margins. A business that benefited from temporarily low input prices.

Normalization adjustments ensure the buyer values the business based on what it would cost to run it properly, not based on unsustainable arrangements.

What QoE is not

A few clarifications that may help if you are encountering this for the first time:

QoE is not an audit. Auditors assess whether accounts comply with accounting standards. QoE advisors assess whether those accounts, properly understood, represent what a buyer is acquiring. There is overlap, but the purpose is different.

QoE is not just add-backs. A common misconception is that QoE means adding back costs to inflate EBITDA. In practice, adjustments go both ways. A TS report might identify items to add back (favorable to the seller) and items to deduct (favorable to the buyer). The goal is accuracy, not advocacy.

QoE is not a forecast. Quality of Earnings looks backward to establish a baseline. It answers the question: what did the business earn, adjusted for distortions? Forecasting answers a different question: what will it earn in the future? They are related but distinct exercises.

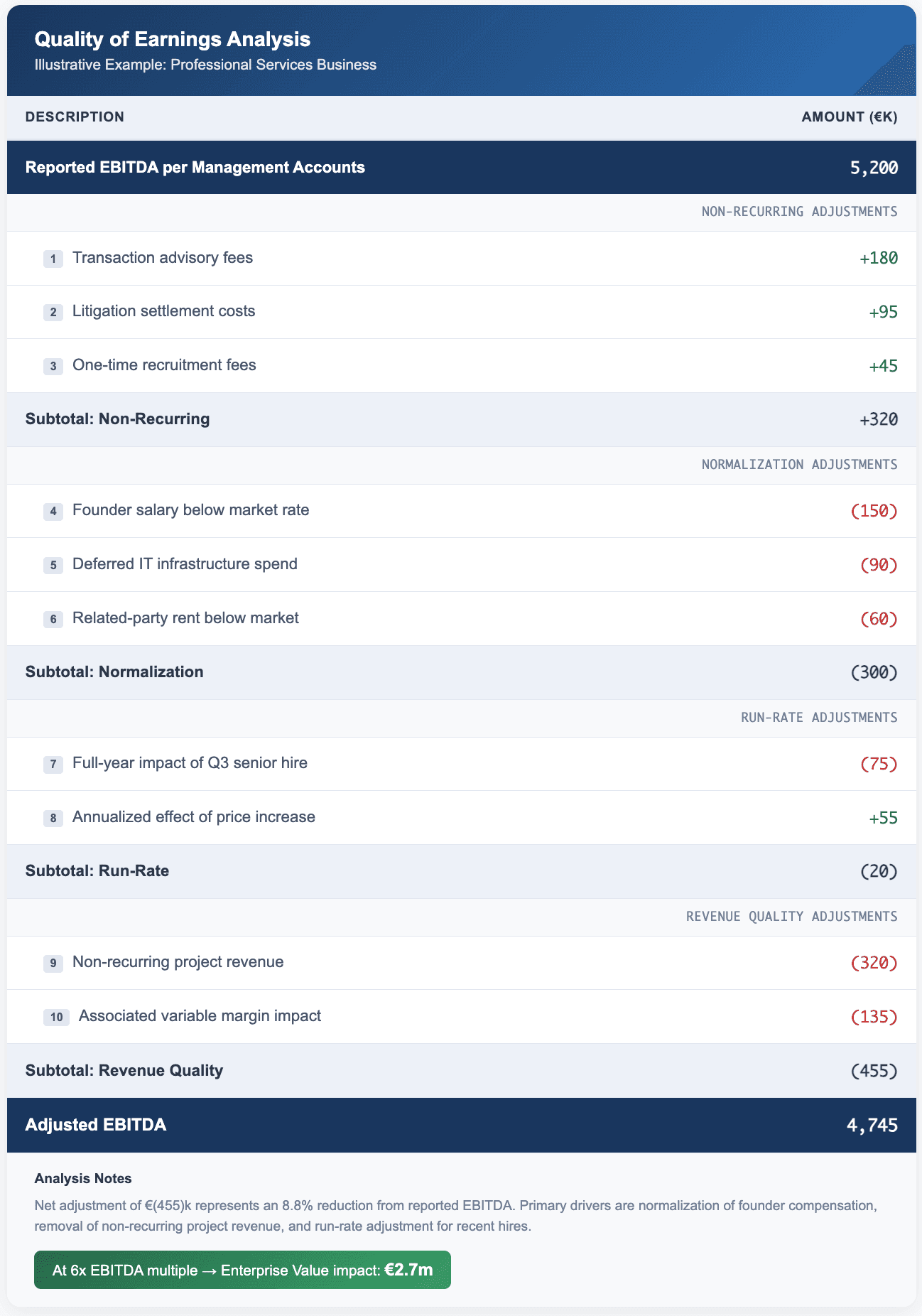

An illustrative example

Consider a professional services firm preparing for sale. The company reports €5.2 million EBITDA in its most recent fiscal year.

The TS advisor reviews the accounts and identifies the following:

Item | Adjustment | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

Transaction advisory fees | +€180k | One-time costs related to the sale process |

Founder salary below market | -€150k | Owner paid himself €100k; market rate is €250k |

One-off project revenue | -€320k | Large engagement with no follow-on potential |

Deferred IT spend | -€90k | Infrastructure costs pushed to next year |

New senior hire (partial year) | -€75k | Full-year salary impact not yet in the numbers |

The net effect of these adjustments is a reduction of €455,000. Adjusted EBITDA is €4.75 million, not €5.2 million.

At a typical services multiple, say 6x EBITDA, this difference represents nearly €3 million of enterprise value. It changes what a buyer should bid. It changes what a lender will finance. It changes the economics of the entire deal.

How buyers and investment committees think about QoE

If you work in transaction services long enough, you start to understand what matters to the people who make investment decisions. Here is how I would describe their mindset:

They care about maintainable cash flow. PE funds model returns based on cash available for debt service and distributions. Reported EBITDA is a starting point, but adjusted EBITDA is the input to the model. If the adjustment analysis is weak, the model is wrong.

They discount one-off add-backs aggressively. Investment committees have seen too many deals where sellers classified ordinary business fluctuations as "exceptional." If an adjustment feels like a reach, expect buyers to push back hard or simply not credit it.

They focus on the direction of adjustments. A QoE analysis that shows €500k of add-backs and €200k of negative adjustments tells a different story than one where everything moves in the seller's favor. Credibility matters.

They use QoE to inform the price mechanism. Adjusted EBITDA often flows directly into the enterprise value calculation. But QoE findings also inform working capital targets, net debt definitions, and SPA protections. A clean QoE report means fewer surprises at completion.

Why this matters in a transaction

Quality of Earnings is not an academic exercise. It feeds directly into the economics of a deal.

The adjusted EBITDA figure becomes the valuation anchor. Multiply it by the agreed multiple, and you have enterprise value. Subtract net debt, adjust for working capital, and you arrive at equity value. Every million of EBITDA adjustment translates directly into enterprise value.

Beyond valuation, QoE findings shape the transaction documents. Adjustments that are contested might trigger warranty claims. Items flagged as uncertain might require escrow protection. Patterns observed in historical earnings might influence earn-out structures or completion account definitions.

A strong QoE analysis does not just establish a number. It provides the evidentiary basis for how risk is allocated between buyer and seller.

Closing thoughts

Quality of Earnings analysis exists because financial statements, while necessary, are not sufficient for making investment decisions. Accounting standards are backward-looking. They permit choices. They aggregate items that should be disaggregated. They do not answer the question a buyer actually asks: what am I buying, and what will it earn for me?

If you are learning transaction services, this is the first concept to truly internalize. Everything else, from working capital to net debt to completion mechanisms, builds on a foundation of understanding what the business actually earns.

The reported number is where the conversation starts. The adjusted number is where it ends.

This is Part 1 of a 5-part series on Quality of Earnings. Upcoming articles will cover the mechanics of adjustment identification, revenue quality assessment, cost structure analysis, and how QoE findings shape deal outcomes.